Skilled Nursing Facilities provide a much-needed service, and apart from the occasional deliberate bad apple—which is not our concern here—the most common problems encountered in the industry are non-deliberate errors in accounting, billing, and coding, all of which can and do lead to incidents of fraud, waste, and abuse. While not intentional, errors of this sort can—and often do—have serious consequences for facilities, so it is imperative that systems are put in place to reduce their incidence as far as humanly possible.

As CMS has said in its “Program Integrity and Quality of Care—An Overview for Nursing Home Providers” Nursing Home Toolkit, understanding how fraud, waste, and abuse occurs “can help providers avoid errors that could cause problems for themselves or the facilities in which they work.”

Fraud is the most obvious issue which SNFs face. This is officially defined in the Medicaid literature as “an intentional deception or misrepresentation made by a person with the knowledge that the deception could result in some unauthorized benefit to himself or some other person.”

Billing for unnecessary services or items is the most common form of Medicare and Medicaid fraud. However, this can occur through error rather than intended fraud—but even if that is that case, the consequences are the same. Combatting unintentional billing errors should be a high priority for any SNF.

Waste is not specifically defined in Medicaid program integrity rules but is generally understood to encompass the over utilization or inappropriate utilization of services and misuse of resources, and typically is not a criminal or intentional act. Examples of waste include a provider ordering more medical supplies than the beneficiary needs or ordering excessive laboratory tests.

Abuse can be defined as “careless or unprofessional business and healthcare practices that result in unnecessary or excessive charges to Medicaid, billing and receiving payment for medically-unnecessary services, and substandard care. It can also include beneficiary behavior (for example, doctor shopping) that unnecessarily increases costs to Medicaid.”

Although waste and abuse do not require the intention to illegally profit from the Medicaid program, penalties can still be issued against a facility. A rigorous system of compliance and cross-checking needs to be in place to ensure that:

(a) Only medically-necessary services or supplies are billed to Medicaid or Medicare;

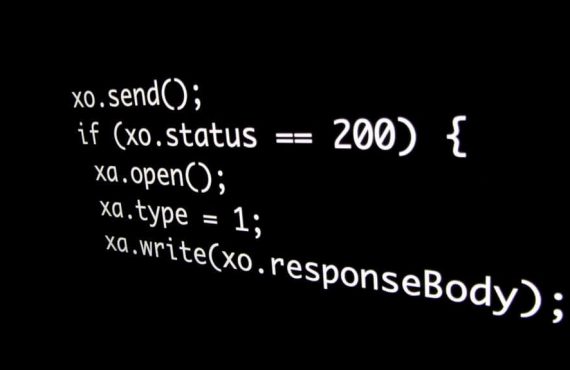

(b) No billing code errors creep in;

(c) All staff understand clearly the need for accurate record keeping and correct billing—and the consequences of failure in this regard;

(d) All services billed are in fact authorized by Medicare and Medicaid cover;

(e) Billed-for services are in fact delivered to the standard required by the CMS. For example, if conditions at the SNF are below those demanded by the CMS, then this officially qualifies as fraud. This also applies to instances of inadequate staffing, no nursing or housekeeping supplies, food shortages, poor sanitary conditions, and “hazardous physical environments.”

(f) No “upcoding” errors occur. Upcoding is the billing for services at a level of complexity higher than the service actually provided. This might often not be intentional, for example, billing Medicare for 45 minutes of individual therapy when the actual therapy time was 30 minutes.

(g) No “unbundling” errors occur. This is also an often unintentional error whereby a facility might order a panel of tests on a resident, and instead of appropriately bundling the tests and billing for them together, each test is billed separately.

(h) No “kickbacks” occur. While “kickbacks” are most commonly associated with deliberate fraud, it is often not known or understood by staff that even seemingly innocuous gifts can be interpreted as kickbacks by a CMS investigation.